Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Some Caroline Walker Bynum

Here's a fantastic lecture by Caroline Walker Bynum regarding the 'stuff' of religious miracles in the Middle Ages. If you have an hour to kill, you're in for a treat!

A Softer, More Feminine Christ

We (and by 'we,' I mean Western folk) think in binary. Light/dark. Good/evil. Man/woman. Gay/straight. Harry Potter/Voldemort. Thinking of things on a continuum is a stretch for some after thinking this way for so long, which -I think - is a reason why people take issue with the idea of a feminine Christ figure. There's no ambiguity in terms of the sex of the Christ figure, but gender poses questions. Gender, after all, is merely a social construct. What it means to be masculine or feminine today meant something different 500, 1000, 2000, 5000 years ago - and, of course, there doesn't historically seem to be much wiggle room or grey area in the Western tradition. Females were/are expected to live up to societal standards for women and males were expected to live up to societal standards for men. Of course, it would be anachronistic to apply current standards to historical figures. But what about roles that haven't changed throughout the ages?

Julian of Norwich, who I discussed briefly in my last post, discussed at length in her writings the idea of Christ as woman and mother after her visions of him on, what she assumed, was her deathbed. It's not uncommon for people to seek similarities to those who play a sizable role in their lives - or, in Julian's case, to look for the feminine and womanly in Christ. Consider the blood of Christ - he shed blood to give new life. Sound familiar? A woman's menstrual cycle signals her life-giving ability. Additionally, women shed blood during labor. These facts did not go unnoticed by Julian of Norwich or other intellectual women of the time. These thoughts are recorded in their writings - in The Showings of Julian of Norwich, for example.

Additionally, Julian's theology was controversial in regard to her belief in God as mother. Some scholars believe this is a metaphor rather than a literal belief or dogma. In her fourteenth revelation, Julian writes of the Trinity in domestic terms, comparing Jesus to a mother who is wise, loving, and merciful. Julian's revelation revealed that God is our mother as much as He is our father. On the other hand, some scholars assert that Julian believed that the maternal aspect of Christ was literal, not metaphoric; Christ is not like a mother, He is literally the mother. Julian believed that the mother's role was the truest of all jobs on earth. She emphasized this by explaining how the bond between mother and child is the only earthly relationship that comes close to the relationship one can have with Jesus. She also connects God with motherhood in terms of (1) the foundation of our nature's creation, (2) the taking of our nature, where the motherhood of grace begins and (3) the motherhood at work, and writes metaphorically of Jesus in connection with conception, nursing, labor, and upbringing.

These are, indeed, revolutionary writings considering the time period and author. Why were they permitted? By virtue of her position in the church, Julian of Norwich could seemingly write whatever she wanted. She was an anchor, that is, she lived in an anchorhold on the side of St. Julian's Church in England. She devoted her life to contemplation. Julian lived an ascetic lifestyle and devoted herself to Christ. By removing herself from domestic life, severely restricting her food intake (thus, stopping menstruation), and developing her intellect, among other things, she was able to effectively become genderless. Her writings had more authority and were tolerated by the Church.

Whether or not Julian's efforts were intentional or not, perhaps they enabled her to envision a more androgynous Christ figure, a Christ figure whose qualities were either both manly and womanly or neither. It would be anachronistic for me to apply the term, "feminist," to Julian -although she has greatly influenced feminist theology- but this notion is dripping with the ideas of negative and positive androgyny. Personally, I'm of the camp that preaches that traits have no gender; women can certainly be aggressive, men can certainly be passive, we think this way because of social conditioning, etc. Now, I think it's a huge leap to say that this is exactly what Julian of Norwich was writing about, but her ideas about Christ as mother may certainly have influenced future ideals of what gender entails.

Julian of Norwich, who I discussed briefly in my last post, discussed at length in her writings the idea of Christ as woman and mother after her visions of him on, what she assumed, was her deathbed. It's not uncommon for people to seek similarities to those who play a sizable role in their lives - or, in Julian's case, to look for the feminine and womanly in Christ. Consider the blood of Christ - he shed blood to give new life. Sound familiar? A woman's menstrual cycle signals her life-giving ability. Additionally, women shed blood during labor. These facts did not go unnoticed by Julian of Norwich or other intellectual women of the time. These thoughts are recorded in their writings - in The Showings of Julian of Norwich, for example.

Additionally, Julian's theology was controversial in regard to her belief in God as mother. Some scholars believe this is a metaphor rather than a literal belief or dogma. In her fourteenth revelation, Julian writes of the Trinity in domestic terms, comparing Jesus to a mother who is wise, loving, and merciful. Julian's revelation revealed that God is our mother as much as He is our father. On the other hand, some scholars assert that Julian believed that the maternal aspect of Christ was literal, not metaphoric; Christ is not like a mother, He is literally the mother. Julian believed that the mother's role was the truest of all jobs on earth. She emphasized this by explaining how the bond between mother and child is the only earthly relationship that comes close to the relationship one can have with Jesus. She also connects God with motherhood in terms of (1) the foundation of our nature's creation, (2) the taking of our nature, where the motherhood of grace begins and (3) the motherhood at work, and writes metaphorically of Jesus in connection with conception, nursing, labor, and upbringing.

These are, indeed, revolutionary writings considering the time period and author. Why were they permitted? By virtue of her position in the church, Julian of Norwich could seemingly write whatever she wanted. She was an anchor, that is, she lived in an anchorhold on the side of St. Julian's Church in England. She devoted her life to contemplation. Julian lived an ascetic lifestyle and devoted herself to Christ. By removing herself from domestic life, severely restricting her food intake (thus, stopping menstruation), and developing her intellect, among other things, she was able to effectively become genderless. Her writings had more authority and were tolerated by the Church.

Whether or not Julian's efforts were intentional or not, perhaps they enabled her to envision a more androgynous Christ figure, a Christ figure whose qualities were either both manly and womanly or neither. It would be anachronistic for me to apply the term, "feminist," to Julian -although she has greatly influenced feminist theology- but this notion is dripping with the ideas of negative and positive androgyny. Personally, I'm of the camp that preaches that traits have no gender; women can certainly be aggressive, men can certainly be passive, we think this way because of social conditioning, etc. Now, I think it's a huge leap to say that this is exactly what Julian of Norwich was writing about, but her ideas about Christ as mother may certainly have influenced future ideals of what gender entails.

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Moon Link

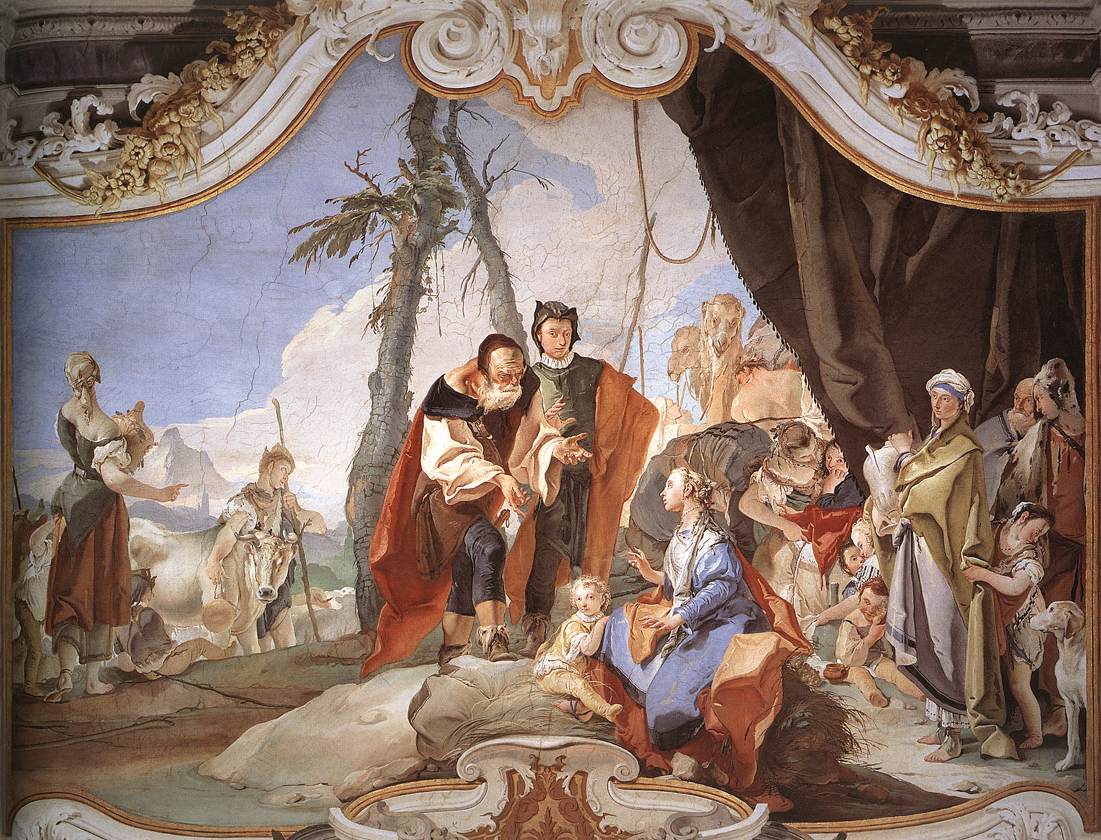

So, I'm currently on my period and this thought occurred to me: the title of my blog is the red tent, where menstruating women hung out, yet I've never wrote about menstruation in terms of society and religion. Gender in the realm of religion is one of my favorite academic topics; what kind of scholar would I be if I didn't bring up menstruation? One of my very favorite passages in the Old Testament involves Rachel's escapades in the red tent: in the spirit of seeking revenge on her father, Laban, Rachel steals his household idols. When he comes looking for them, she places them under a sitting pillow in the red tent. Laban enters the red tent and demands to know where his idols are and Rachel replies, "It is my woman's time," or some such. Laban understands instantly and leaves. How clever Rachel is! (Some might say that she is being a tricky, deceptive woman, but no such judgmental statements are actually made like that in the passage. One more reason the J sections of the OT were penned by a woman.)

|

| Rachel Hiding the Idols from Her Father Laban by Giambattista Tiepolo |

While we're being upfront, I should tell you that I have a gynecological disorder called dysmenorrhea, or, more simply, menstrual pain. Symptoms include extreme lower abdominal, back, and leg pain, excessive bleeding, nausea, fatigue, dizziness and disorientation, migraines, fainting, difficult bowel movements, and hypersensitivity to light, smell, sound, and touch. It's incredibly unpleasant to say the least. Thus far in life, the only relief I've gotten from symptoms is from NSAIDS, heating pads, PMS Tea, and hormonal birth control. In fact, since I started taking birth control 7 years ago - when I was 15 - the symptoms have been limited to mild cramping and fatigue, crazy mood swings and hunger pangs, the occasional migraine, and on and off sexual cravings. I imagine that's what it's like for most women, though. It's fantastic!

Now, how does this all relate? In addition to my love of the formative history of Judaism, I am also quite fond of Medieval Christianity and the lives of female contemplatives in particular. I imagine that, if I were alive during the Middle Ages, my symptoms might have been interpreted quite differently than people see them today. More specifically, such symptoms might denote me as some sort of mystic, a witch, or perhaps the victim of a witch. Indeed, if one were to read accounts of any of these figures today, one could attribute mystical or magical abilities to any sort of common malady. For example, if a female anchor were to recount an ecstatic experience with Jesus, one might conclude that she is actually afflicted with epilepsy and is merely having a seizure. Or, if I were observed by to typical Medieval folk while I was tossing in turning in bed, moaning in pain, vomiting everywhere, and then lose consciousness, they might think a) I was filled with Christ's presence, b) I was possessed by Satan, or c) a witch had cast a spell over me/I was a witch. Some might interpret the dreams and hallucinations I had while passed out at visions from God. I might, like Julian of Norwich, have the opportunity to record my experiences and interpret them as elaborate philosophy on Christ's femininity - I'll discuss Julian's writings later.

|

| The original cat lady |

There's no denying that menstruation was and is seen by many as some sort of disgusting, unnatural function of the woman's body. Who hasn't heard the very clever phrase, "Women are the only animals that can bleed for 7 days and not die. They must be evil," or some such poppycock. Historically speaking, when men bled, it was because they were doing something masculine - like receiving a war wound. A bleeding man was an honorable one, he shed blood for God or his king or country.

|

| For example... |

When women bled, however, there seemed to be no rhyme or reason or uniqueness, for every woman bleeds. Furthermore, to add to the 'grossness' of it all, menstrual blood exits via the vagina, a vile, swamp-like place. The vagina was the indicator of the female sex and, after all, females were (are?) considered the cause of evil. Eve caused the Fall of Man. Sheba tempted David. Delilah cut Samson's hair. Helen caused the Trojan War. I could go on, but the point is that women were dirty creatures and the vagina was the apex of filth. It was for procreation only.

Of course, this is somewhat hyperbolic and not the sole reason for all the misogyny in the world, but, in my opinion, this mindset helps account for some of it. There are plenty of people today who thing vaginas are disgusting for various reasons - because they're wet, they emit (completely natural and useful) discharge, they release menstrual fluid, they're flexible, they're hairy on the outside, it's tunnel-like and you can't see where it goes, etc. For centuries, nobody knew for sure how reproduction worked, they just knew if menses didn't occur after a sexual encounter, the woman was pregnant. Some proto-scientists believed woman was just merely a vessel and man's seed carried all the ingredients to implant a baby in the womb. Yes, woman's reproductivity was a mystery to many. But why did mystery have to mean evil?

|

| Have a happy period. |

Anyway, I think that's it for now. In my next post, I'll discuss the idea of a feminine Christ figure as presented by Julian of Norwich.

Wednesday, June 29, 2011

Back to Black

For those of you who might be reading, it's been a hectic semester/beginning of summer. I've decided to return to the Red Tent. Writing is cathartic and I'm going to commit to blogging more. Catharsis is something I need while having roofers tear up my roof as we speak.

So, what have I been doing? This last semester, I was enrolled in Femininity in Early Modern France, Human Prehistory, History of Modern France, and Philosophy of Feminism. Typical. I did well in them all and am satisfied with my grades.

I moved in with lover at the beginning of summer. We are living in delicious sin.

So, where do I envision this blog going? I'm still going to keep with the themes of religion and constructions of gender. I will probably throw in musings on politics, pop culture, history, literature, and food because they are quite central to my life. Since this blog no longer has any academic requirements, it has the potential to go anywhere. So, here's some Amy Winehouse-

I'm currently reading three books simultaneously - A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith, Walking the Bible by Bruce Feiler, and The Five Books of Miriam: A Woman's Commentary on the Torah by Ellen Frankel. Let's nevermind Smith's work for now (I'll get back to it eventually, promise). The other two works focus primarily on the Torah. Feiler attempts to find the geographical locations highlighted in the first five books of the Bible - the Cave of the Patriarchs, the well where Jacob met Rachel, the precise spot where the Hebrews crossed the Red Sea, etc. The book also documents Feiler's effort to connect with his faith. Culturally Jewish, Feiler mentions several times in the text that he feel some special link to the Levant.

It's a compelling idea that's also present in the Frankel text. Her book relies on this notion of sisterhood among Jewish women. The commentary is presented in question form; that is, a passage from the Torah is summarized and questioned are asked about it. These questions are answered by various Biblical/mythical figures - Lilith, Eve, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, Leah, Dinah, and so on - as well as characters such as the Rabbis who composed Midrash (commentary on the Torah) and our Jewish grandmothers and mothers. It's filled with both academic facts and maternal wisdom. Frankel pays special attention to the role of gender in the Torah, a topic upon which there has been much scholarship, and is able to present it in a palatable manner.

Both of these pieces are fantastic so far. My only problem - and this is something that nothing new - is that both of these texts rely upon a spiritual worldview. Both authors insert their personal religious beliefs into their writing, which is fine. As a scholar and an atheist, however, it is my job to parse out what these writers are presenting as fact and what they're presenting as their own beliefs. It doesn't particularly bother me any if someone truly and completely believes that Moses wrote the Torah himself (which neither of these writers posits, just fyi), but it does help me to know why people believe that and how it informs their spirituality.

I'll keep you posted when I finish these bad boys and can give a complete report! Until next time...

So, what have I been doing? This last semester, I was enrolled in Femininity in Early Modern France, Human Prehistory, History of Modern France, and Philosophy of Feminism. Typical. I did well in them all and am satisfied with my grades.

I moved in with lover at the beginning of summer. We are living in delicious sin.

So, where do I envision this blog going? I'm still going to keep with the themes of religion and constructions of gender. I will probably throw in musings on politics, pop culture, history, literature, and food because they are quite central to my life. Since this blog no longer has any academic requirements, it has the potential to go anywhere. So, here's some Amy Winehouse-

I'm currently reading three books simultaneously - A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith, Walking the Bible by Bruce Feiler, and The Five Books of Miriam: A Woman's Commentary on the Torah by Ellen Frankel. Let's nevermind Smith's work for now (I'll get back to it eventually, promise). The other two works focus primarily on the Torah. Feiler attempts to find the geographical locations highlighted in the first five books of the Bible - the Cave of the Patriarchs, the well where Jacob met Rachel, the precise spot where the Hebrews crossed the Red Sea, etc. The book also documents Feiler's effort to connect with his faith. Culturally Jewish, Feiler mentions several times in the text that he feel some special link to the Levant.

It's a compelling idea that's also present in the Frankel text. Her book relies on this notion of sisterhood among Jewish women. The commentary is presented in question form; that is, a passage from the Torah is summarized and questioned are asked about it. These questions are answered by various Biblical/mythical figures - Lilith, Eve, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, Leah, Dinah, and so on - as well as characters such as the Rabbis who composed Midrash (commentary on the Torah) and our Jewish grandmothers and mothers. It's filled with both academic facts and maternal wisdom. Frankel pays special attention to the role of gender in the Torah, a topic upon which there has been much scholarship, and is able to present it in a palatable manner.

Both of these pieces are fantastic so far. My only problem - and this is something that nothing new - is that both of these texts rely upon a spiritual worldview. Both authors insert their personal religious beliefs into their writing, which is fine. As a scholar and an atheist, however, it is my job to parse out what these writers are presenting as fact and what they're presenting as their own beliefs. It doesn't particularly bother me any if someone truly and completely believes that Moses wrote the Torah himself (which neither of these writers posits, just fyi), but it does help me to know why people believe that and how it informs their spirituality.

I'll keep you posted when I finish these bad boys and can give a complete report! Until next time...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)